옹기 (Onggi), breathing vessel.

Kyungtae Kwak has long been fascinated with the craft of creating traditional Korean ceramic vessels through

both the 옹기

(Onggi) and

분청 (Buncheong) methods. Based in the small city of Icheon, Kwak teaches and works

as a ceramics artisan with a focus on Korean slipware. He's known in craft circles for his somewhat

unconventional approach of mixing elements of the old Korean styles he works with to forge something unique and

modern. But that's not to say his work betrays the form or the storied past of Korean craft. Kwak's approach

honours the art of ceramics and the natural imperfections that arise in the making process, embracing the

changeable elements of the clay he works into his characterful, but pared-back wares.

The work of Mexico's

Frida Escobedo's architecture firm also tends to challenge boundaries in

interesting and thoughtfully planned ways. With a strong focus on materiality and forming compelling

narratives in her architecture, Escobedo's celebrated portfolio ranges from

Aesop

interiors in New York (where she imported rammed earth bricks from her native Mexico into cosmetics company's

Brooklyn outpost - forming a unique dialogue between these two destinations in her design) to the 2018

Serpentine Pavilion in London.

Escobedo and Kwak

speak about the ceramic making process and how closely linked craft and architecture can be.

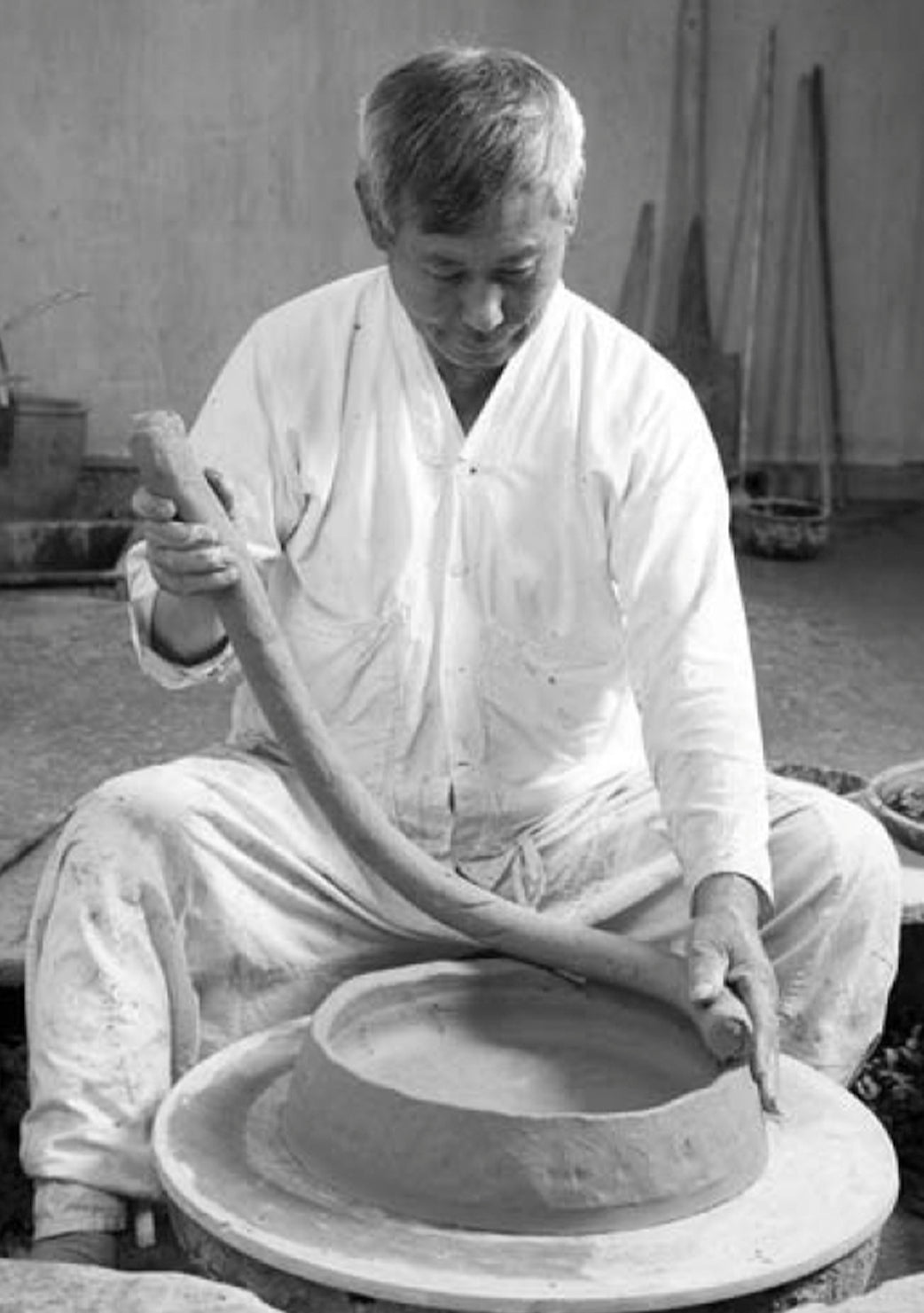

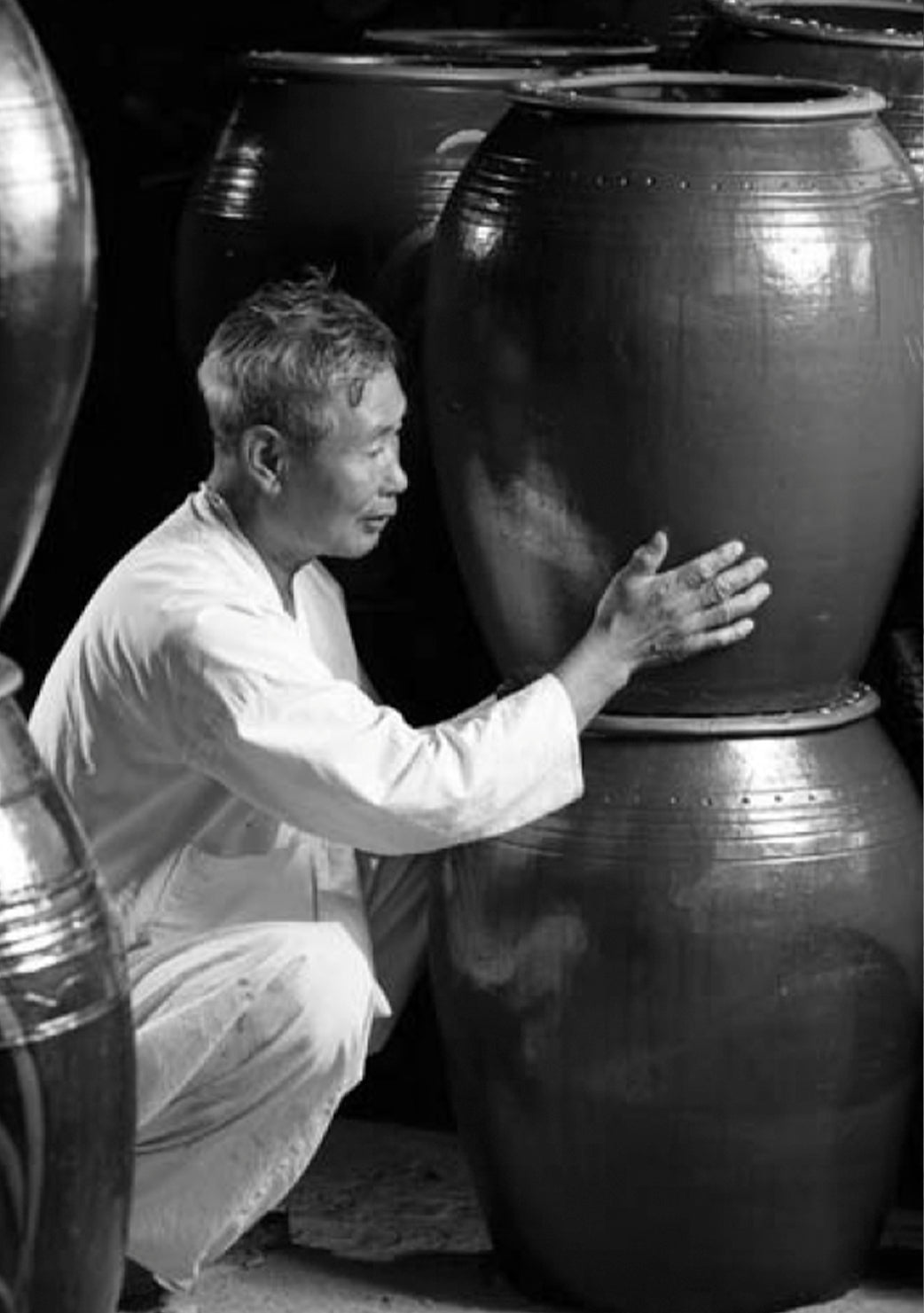

- 1. 옹기 (Onggi) vessels ready to be glazed

- 2. 분청 (Buncheong) technique on an onggi vessel

- 3. 옹기 (Onggi)vessels by Kyungtae Kwak

1.

2.

3.

1. 옹기

(Onggi) vessels ready to be glazed

2. 분청

(Buncheong) technique on an onggi vessel

3. 옹기

(Onggi)vessels by Kyungtae Kwak

- 옹기 (Onggi), breathing vessel.

Kyungtae Kwak has long been fascinated with the craft of

creating traditional Korean ceramic vessels through both the 옹기 (Onggi) and 분청 (Buncheong) methods. Based in the small city of Icheon, Kwak teaches and

works as a ceramics artisan with a focus on Korean slipware. He's known in craft circles for his somewhat

unconventional approach of mixing elements of the old Korean styles he works with to forge something unique

and modern. But that's not to say his work betrays the form or the storied past of Korean craft. Kwak's

approach honours the art of ceramics and the natural imperfections that arise in the making process, embracing

the changeable elements of the clay he works into his characterful, but pared-back wares.

The work of Mexico's Frida Escobedo's architecture firm also tends to challenge

boundaries in interesting and thoughtfully planned ways. With a strong focus on materiality and forming

compelling narratives in her architecture, Escobedo's celebrated portfolio ranges from Aesop

interiors in New York (where she imported rammed earth bricks from her native Mexico into cosmetics

company's Brooklyn outpost - forming a unique dialogue between these two destinations in her design) to the

2018 Serpentine Pavilion in London.

Escobedo and Kwak speak about the ceramic making process

and how closely linked craft and architecture can be.

Kyungtae Kwak

Frida Escobedo

Illustrations by

Jiye Kim

- My name is Frida Escobedo I have an architecture studio in Mexico City. We do residential, hospitality

and retail projects but we’re also very interested in the intersection between art and architecture or

art and design. This one of the reasons I wanted to have this conversation because we have both have

practices that try to expand a little bit out of the boundaries within our disciplines. So it’s a

pleasure to talk to you - I don’t have a very deep knowledge of ceramics though, but I have always been

fascinated by the craft because I find so many intersections in the way it is conceptualised in

architecture.

- To introduce myself, I’m an 옹기 'Onggi' (A traditional Korean

earthenware) maker based in the city of Icheon in Korea. Icheon is located around 50 kilometres

south of Seoul and is known as the nation’s city of ceramic making capital. There are around 200

ceramicists based here and I’m one of the Onggi ceramic makers.

I would like to start with the idea that architecture and pottery are very much related. I was reading

about Theaster Gates, an artist based in Chicago, who started his career as a potter but now works at the

intersection between space design and art. He has a very interesting practice because he’s always working

with this idea of cultural identity. As a black artist – he has been working in Chicago, not just on regular

art pieces, but also doing renovations in neighbourhoods in cultural centres and better activating spaces.

So, this idea of a container goes beyond smaller scales and into the urban and architectural realms, but he

still sees them in very similar ways.

Gates still practices pottery sometimes and in the interview, I was reading about he

talks about how the pottery has allowed him to understand this idea of the creation of both a container

and an instrument. And I think that’s the main relationship with architecture - we create physical spaces

to contain but also that become instruments for transformation and social interaction. So do you see some

sort of relationship between this idea of an object, actually containing something else in the way that

architecture does?

- I agree that ceramics can be used as a vessel, but also as an instrument. In Korea, ceramics were

first created during the ‘Three Kingdoms’ period - around 18 BC - and have continued to develop since

then. Onggi ceramics, which I specialise in, were first used for eating

purposes, and as containers to ferment foods in. In the past, every Korean household would have around

20 to 30 onggi to ferment soy sauce, and 고추장 (gochujang) – red chilli pepper paste placed in their back garden – this

space where they all sat together was called 장독대 'Jangdokdae’. This

still occurs today. When you have many 옹기 onggi gathered together, it’s

quite a sight, and over time Jangdokdae has become part of our architecture. Now in Korea tourists go to

farms, or temples where there are still this Jangdokdae – just to see this scene, where onggi are all

gathered together.

So I think onggi and architecture are quite

alike. Today, the purpose of ceramics is changing. Traditionally, it was made simply to be used but

nowadays it’s also become an object that can be just admired. It’s a similar case for architecture, as

people initially made a mud hut for shelter but architecture later developed into something that had

an element of beauty to it that would also be made to be admired.

"In the past, every Korean household

would have around 20 to 30 onggi to ferment soy sauce, and 고추장 gochujang – red chilli pepper paste placed in their back garden – this

space where they all sat together was called 장독대 'Jangdokdae’. This

still occurs today. When you have many 옹기 onggi gathered together, it’s

quite a sight, and over time Jangdokdae has become part of our architecture."

4. The

unique texture is done by mixing buncheong technique with an onggi vessel

5. Tools used for onggi vessels

- I guess it has to do with this idea of use-value but also a symbolic value. With pottery itself and

there’s an added factor, which is this special relationship with locality. Ceramics are made with the soil

and the minerals and then there’s this process that transforms the matter and then it turns into something

beautiful. But it’s beautiful because it’s telling a story, it has a narrative to it. It’s not just about

aesthetics - the aesthetic of the object tells a story.

- Yes – and that aesthetic story differs based on locality, the way people even use onggi regionally is all different.

I am also interested in your efforts to mix two different Korean techniques in your work

– buncheong and onggi - you are creating something new. It’s like taking the

craft to the future and it’s adding value instead of eroding it. I think that’s a similar way to how I

approach my work – because we’re always interpreting what we see and we’re building a language upon words

that have been created in the past. It’s just a matter of arranging them in ways and translating and

transforming them so it becomes very much of a geographic landscape and that’s why I’m so fascinated by

these ‘layers’.

- I guess I’m trying to find my approach – and one way has been to introduce a technique that does not

belong with traditional onggi making into my process. With my work, I

glaze onggi with buncheong technique. This means the glazing is

different to the normal onggi glaze, because the buncheong glazing

technique uses white clay. And what makes it more interesting is once you’ve added this layer of the

white clay, you get much more unexpected colour variations once it goes under fire.

I’m also interested in this idea of mastering a craft through repetition. There's a quality to this very

specific form of ceramics that you work on that has an element of surprise and unexpectedness. For example,

when you are doing 20 pots for a specific project, there must be very subtle variations within those 20

because of the way you make. For you, what’s the limit between control and the surprise of these variations

and how does the balance between them feed into this idea of mastering craft? What’s that in-between point

between surprise and control?

- When I was young I learned the craft of onggi without a particular

goal in mind - just by practicing it. And then I started to think about the theory behind the technique

and began to contemplate what kind of artist I want to be in the future. At first, I used to like things

that looked pretty. I used to have a preference for simple and clean materials but as I gained more

expertise my perspective started to change. Instead of something pretty and perfect, I began to

appreciate the natural lines that are naturally created through the onggi making process.

I realised that there’s beauty in

the natural lines that are formed and even though I knew that I could master the technique, what was

more important for me was finding the lines that I like from using the technique. So the way I

practiced the craft started to change before it felt like I was trying to control everything to make a

good product and I was solely focused on achieving that. But the way I work has changed from trying to

control everything to a more loosened and somewhat ‘laid back’ approach. What’s interesting about

ceramics is you’re always learning. For example, yesterday I had a really good fire for glazing

my onggi in my kiln, so I tried the exact same process, the technique

today and I got quite a different result – it’s never the same! Aspects of the making - like using a

wooden kiln - mean you cannot control everything. Also, shapes of the finished work will always be

asymmetrical, because the iron that’s embedded in the soil of onggi pops out from the surface as it gets heated.

"I guess I’m trying to find my approach –

and one way has been to introduce a technique that does not belong with traditional onggi making into my process. With my work, I glaze 옹기 onggi with 분청 buncheong technique.

This means the glazing is different to the normal onggi glaze, because

the buncheong glazing technique uses white clay."

That’s great. I feel like this is also very similar to the practice of architecture, there are so many

elements outside of what you can control at play - so the result is always something more complex than you

planned for. But it’s this complexity that makes the work more beautiful – because again it’s a story about

the process and you can see parts of the process materialise in the specific object. I was wondering if you

could explain which part of the process do you feel is the moment when the matter that you work with for

your onggi changes? Because for me, a potter makes nothing into something.

There’s this moment where soil becomes clay and then the clay is starting to become a vessel. Maybe there

are some specific moments where this transformation is more evident?

- You are right – we create nothing into something. I think the moment I form this clay into a certain

shape, that’s when it becomes an onggi – not when it gets glazed, or

when it’s finished. The Korean soil we use has a lot of iron – so you need to filter this raw soil so

you can use it to create onggi and this plays a role in the outcome.

Even after filtering the sand and waste from the soil for days – it is never 100% clean, so you are

always left with a bit of iron in the soil and this comes out when the onggi goes into the wood kiln. It’s this presence of iron, which affects the

form of the surface and gives it this natural texture.

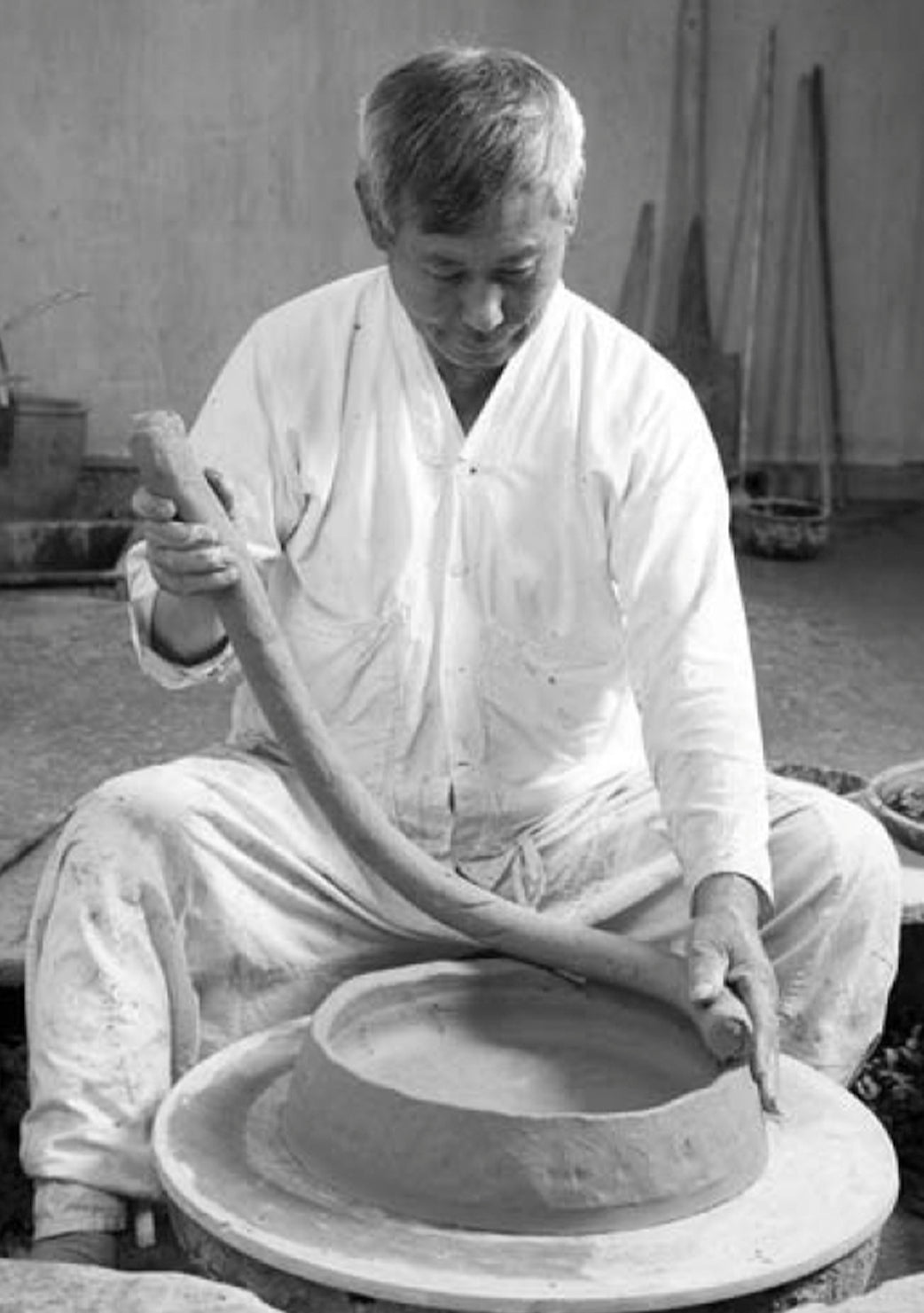

The main difference between

western pottery and Korean pottery and especially for onggi is that

instead of starting with one blob of clay, we coil the clay, so in the beginning, it has a long form.

We put it on our shoulder and then slowly mould it with our hands as we coil it around in front of us

like a snake. As we build it we put a burning torch in the centre, and the rising smoke prevents the

form from breaking or cracking.

It’s interesting because in this coiling process – the clay almost becomes an extension of your body, it

is part of your body weight and you are holding this extension and smoothing it out. What is interesting

about this process – is that it is very alive in the making. You have to be carrying the weight and be very

aware of the moisture of the clay as you are transforming it and building the vessels. It’s almost like this

alchemy. It’s similar to architecture in the sense that we do have specific moments of

transformation. There are always things you can’t control and you have to adapt and pivot and adjust and

react as they happen. But I think with ceramics it is more tangible because you are looking at the object

and seeing how its folds and feeling how it’s drying in front of your own eyes. With architecture, it’s a

little more difficult to perceive because there are so many people involved in the making process and it's

a longer process.

INTERNATIONAL VOICE

FRIDA ESCOBEDO

Forming her eponymous practice in 2006 and realising a

series of remarkable architecture projects in the 15 years since, Frida Escobedo has become a globally sought

after designer for work that creates deep narratives on place, history and materials. While there tends to be

a lightness of touch in her work - reflecting her roots in sunny subtropical Mexico City - the layering of

stories and the deliberate emphasis on applying engaging materials means every project is delivered with a

richness that tends to make them feel like tapestries of her wonderful ideas realised in built form.

KYUNGTAE KWAK

www.ceramicmasterclass.com

FRIDA ESCOBEDO

www.fridaescobedo.com

INTERNATIONAL VOICE

FRIDA ESCOBEDO

Forming her eponymous practice in 2006 and realising a

series of remarkable architecture projects in the 15 years since, Frida Escobedo has become a globally sought after

designer for work that creates deep narratives on place, history and materials. While there tends to be a lightness

of touch in her work - reflecting her roots in sunny subtropical Mexico City - the layering of stories and the

deliberate emphasis on applying engaging materials means every project is delivered with a richness that tends to

make them feel like tapestries of her wonderful ideas realised in built form.

KYUNGTAE KWAK

www.ceramicmasterclass.com

FRIDA ESCOBEDO

www.fridaescobedo.com

Onggi

'옹기'(Onggi)

옹기 (Onggi) is a traditional earthenware vessel in Korea that has been used for

thousands of years as part of the nation's household. Onggi vessels are used

in many different ways from storing fermented foods – famously known for Kimchi - to use as kitchenware, bowls

and pots. Because of the unique way it is made – onggi has become a very coveted item in Korean daily life and

a symbol of country's culture.

The ceramics glazing plays a key role in providing a waterproof surface and preventing leaks. A large

number of sand particles are added to the body of the clay – these become passages allowing air to move freely

through pottery. Onggi is usually fired for about 2-3 days – with the

temperature gradually increased up to 1200 celsius degrees. Once onggi is

fired the crystal water contained in the wall of the pottery vessel is released making the vessel porous,

which allows contents to be stored inside with a longer lifetime. For this reason – onggi was mostly used to ferment food, such as soy sauce, gochujang (chilli pepper paste) and seafood pickles.

Onggi is a natural pottery, it possesses the simplicity of nature but is made

with thousand years of experience and wisdom accumulated by the artisans producing it today. Since plastic and

metal have been introduced, everyday usage of onggi pottery in Korea has been

greatly decreased. Today, however, more people are realising the value of this natural breathing pottery, and

are slowly moving away from what is just easily accessible – to something long-lasting and beautiful to look

at.

1. Before shaping the

onggi vessel, form clay chunks into long and round

tube – roughly 120cm long and 4 cm in diameter, later to be used for shaping the vessel.

2. Take another lump of clay and spread it on top of the wheel.

3. Pad down the clay to the right thickness for the base bottom of the pottery.

4. Build the base with a thin layer of clay and link it with the bottom of the clay.

1. Before shaping the

onggi vessel, form clay chunks into long and round

tube – roughly 120cm long and 4 cm in diameter, later to be used for shaping the vessel.

2. Take another lump of clay and spread it on top of the wheel.

3. Pad down the clay to the right thickness for the base bottom of the pottery.

4. Build the base with a thin layer of clay and link it with the bottom of the clay.

5. Coil the clay tube that was made before slowly around the

onggi

vessel.

6. Slowly coil it further and flatten it as you go.

7. Using both hand with tools – tap outside of the wall to even the thickness and smoothen the surface, this

is called 수레질

'soorejil'.

8. When shaping a large

onggi, place a bucket of wood charcoal burner inside

to dry and prevent the wall of the vessel from collapsing.

5. Coil the clay tube that was made before slowly around the

onggi vessel.

6. Slowly coil it further and flatten it as you go.

7. Using both hand with tools – tap outside of the wall to even the thickness and smoothen the surface, this

is called 수레질

'soorejil'.

8. When shaping a large

onggi, place a bucket of wood charcoal burner inside

to dry and prevent the wall of the vessel from collapsing.

9. Build the

onggi further with ready-made clay tubes.

10.

Onggi is now ready to be glazed.

11. After dried – glaze

onggi with 잿물

(jaetmul) – mixture of pine leaf, grass ashes and soil.

12.

Onggi is fired for 2-3 days (about 45 hours), starting at low

temperature and slowly increasing it up to 1200 degrees celsius which continues on for 30 hours.

9. Build the

onggi further with ready-made clay tubes.

10.

Onggi is now ready to be glazed.

11. After dried – glaze

onggi with 잿물

(jaetmul) – mixture of pine leaf, grass ashes and soil.

12.

Onggi is fired for 2-3 days (about 45 hours), starting at low

temperature and slowly increasing it up to 1200 degrees celsius which continues on for 30 hours.

13.

Onggi master looking at his completed

onggi.

14. 장독대

Jangdokdae – an outdoor space where

onggi vessels sit altogether.

15. Getting the fermented goods from

onggi.

13.

Onggi master looking at his completed onggi.

14. 장독대

Jangdokdae – an outdoor space where onggi vessels sit altogether.

15. Getting the fermented goods from

onggi.

© Images provided by

– Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation

1.

1. 2.

2. 3.

3. 1. 옹기 (Onggi) vessels ready to be glazed

1. 옹기 (Onggi) vessels ready to be glazed 2. 분청 (Buncheong) technique on an onggi vessel

2. 분청 (Buncheong) technique on an onggi vessel 3. 옹기 (Onggi)vessels by Kyungtae Kwak

3. 옹기 (Onggi)vessels by Kyungtae Kwak Kyungtae Kwak

Kyungtae Kwak 4. The

unique texture is done by mixing buncheong technique with an onggi vessel

4. The

unique texture is done by mixing buncheong technique with an onggi vessel 5. Tools used for onggi vessels

5. Tools used for onggi vessels

Frida Escobedo

Frida Escobedo