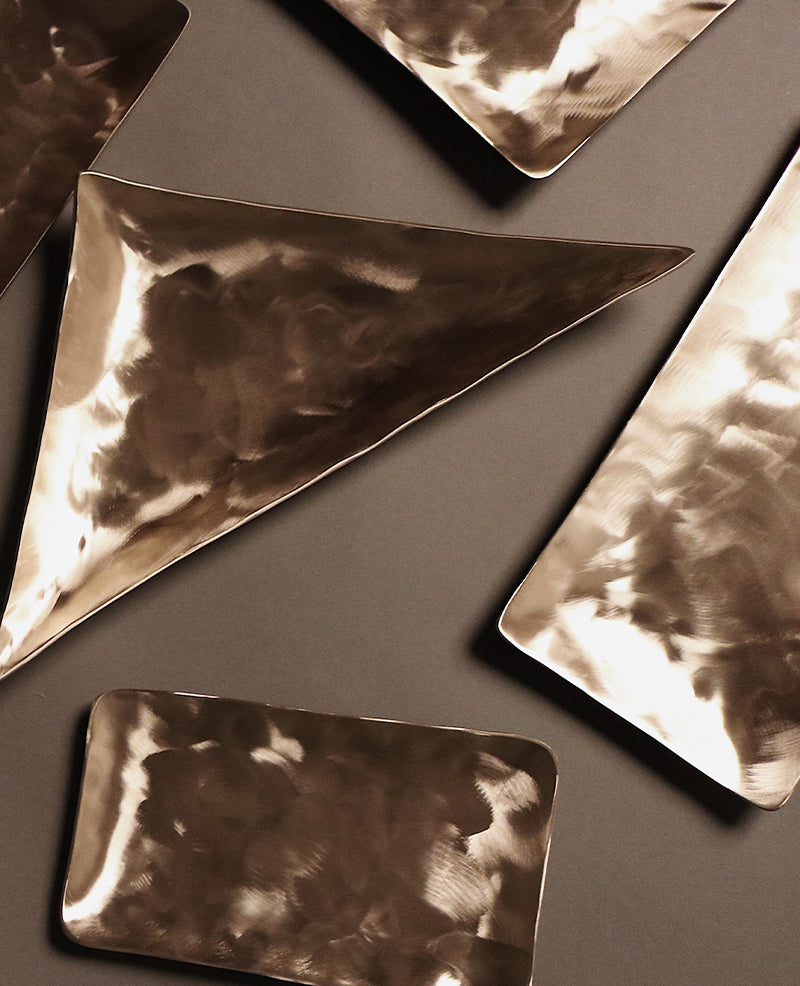

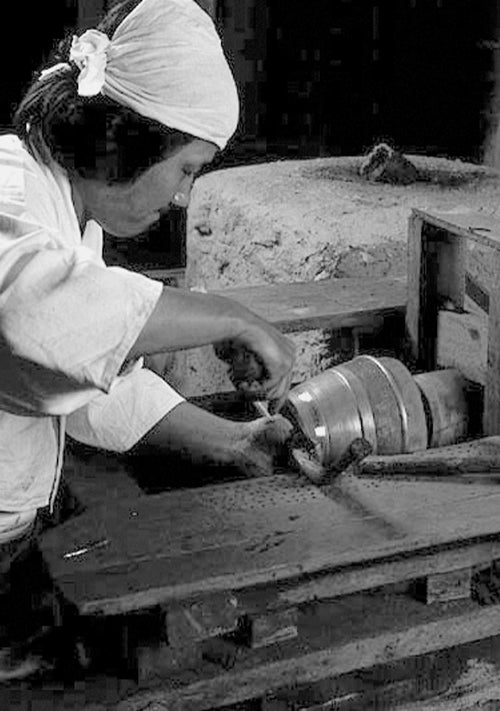

- 1. Hand-forged plates in different forms

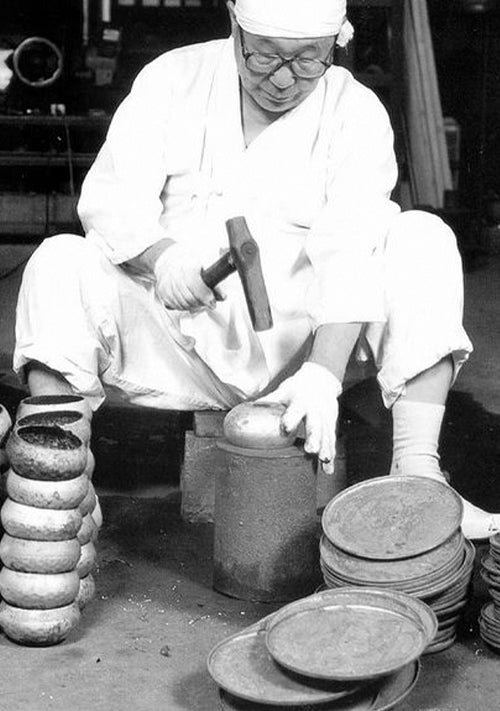

- 2. Traditional Korean spoon and chopstick set

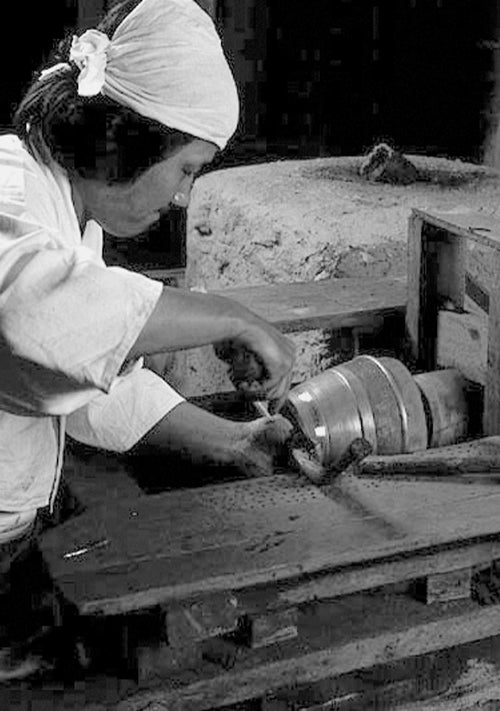

- 3. Detail of 항아리 (hangari)—a small jar with Jong Duk Lee's signature

1.

1. 2.

2. 3.

3. 1. Hand-forged plates in different forms

1. Hand-forged plates in different forms 2. Traditional Korean spoon and chopstick sets

2. Traditional Korean spoon and chopstick sets 3. Detail of 항아리 (hangari)—a small jar with Jong Duk

Lee's signature

3. Detail of 항아리 (hangari)—a small jar with Jong Duk

Lee's signature

- DIALOGUE

- CRAFT INDEX

- 방짜 (Bangjja), homegrown bronzecraft.

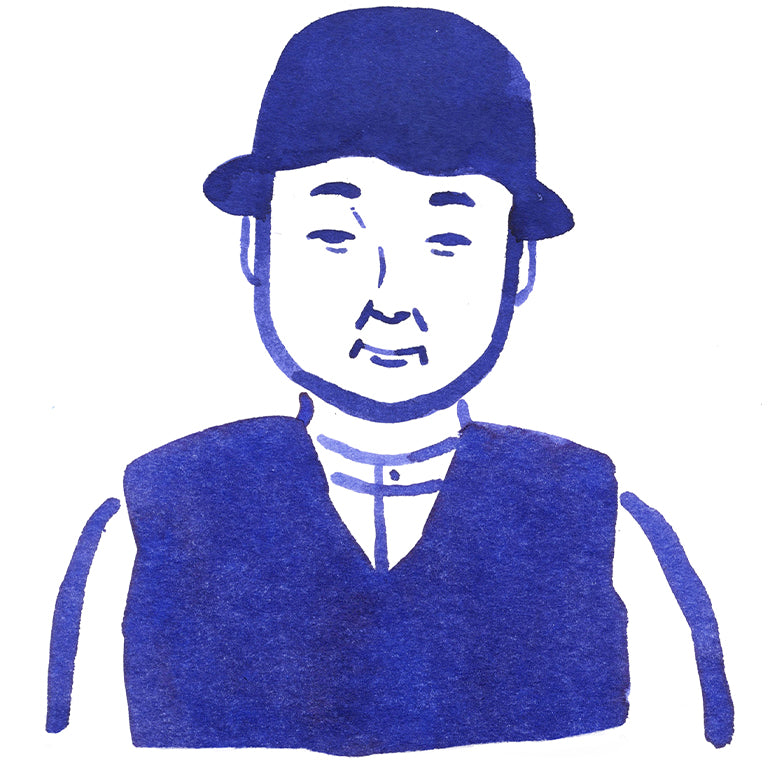

For multiple decades Korea’s Jong Duk Lee has been pursuing perfection in the ancient craft of bangjja, which is a unique form of metal work. Bangjja comes from the Napcheoung region in the country’s north, where it was originally used to make bell instruments and also tableware and crockery. Lee has dedicated much of his life to applying the bangjja technique to traditional instrument and object making, earning an intangible heritage qualification in Korea. He also encourages others to pick up the remarkable craft through education of younger artisans, but today 80% of all the bangjja instruments (such as jing and kkwaenggwari) made in Korea are by Lee.

Based in Tokyo, Ryutaro Yoshida has similarly pursued a career dedicated to craft in Japan as the co-founder of Time & Style - a respected design and furniture brand. It produces pieces for famous architects such as Kengo Kuma and sells its designs through various retailers across the world. For Yoshida, Time & Style is defined by its close relationship to the craft culture of Japan and he enjoys working alongside artisans across the nation to form products that honour the past but are also appealing to a contemporary audience.

With this in mind, Yoshida was interested in speaking with Lee about bangjja, a craft he’s curious to learn more about. It’s also a craft form that could die out – something that Yoshida’s work in Japan aims to prevent for its craftspeople. Younger generations have not been able to move bangjja forward and the Korean government is not giving the craft enough support. But there is immense importance in bangjja - with its incredible history and the meticulous making process behind it, it forms some of Korea’s most beautifully made products, as Yoshida and Lee discuss.

Jong Duk Lee

Jong Duk Lee- I am working with more than 200 artisans all over Japan with various kinds of craft for around 25

years so I’m familiar with the long history and tradition. However, bangjja is a type of craft that

only exists in Korea and I don’t know much about. I am very interested in its history - how long has it

existed? Do you know from where it originated?

- Bangjja craft goes back to Goryeo period (beginning in 918AD), so it has existed for about 1000 years. However, bangjja was not a common craft even all those years ago. I’m aware that some Japanese crafts came from Korea, but the iron casting craft that you are familiar with in Japan was also widely practised in Korea and it is a different technique to bangjja, which was historically used to make tableware for the royal family or to make traditional Korean metal instruments such as jing and kkwaenggwari. There have never been many craftsmen practicing bangjja, but it has survived because it is so important to Korean culture. I believe the technique behind it originally came from India through Silk Road trading, but the specific blend of 78% copper and 22% zinc that forms bangjja has only ever existed in Korea.

- About 40 years ago I used to work for a company that was manufacturing valves and plumbing screws, so I was familiar with jumul (the more popular iron casting craft) and bangjja too. But I was particularly interested in bangjja. I once watched Samul nori (a traditional Korean music form, played with jing and kkwaenggwari as instruments) and I heard the sound and fell in love with it, so I decided I wanted to make the best jing and kkwaenggwari with bangjja in Korea. I started working for a company that was making bangjja, but they were cutting corners to save money and from there wherever I went to learn about bangjja I realised those practising it were not following the traditional way. So I did more research and went to meet people who were on television for being famous for their bangjja craftsmanship and I visited Japan and China because I heard there were masters of the craft there - but no one was doing it the right way. So, I continued to study by myself, looking at jing and kkwaenggwari instruments that have existed from centuries ago, researching them and reading many historical documents. I would practice the techniques behind them over and over in the workshop at the company when everyone else had left for the day. So, by picking out the right technique from all the different sources – after lots of trials and error - I was eventually able to master bangjja craft myself.

- It’s nothing amazing really, making no money, I’m just doing what I love!

- Yes of course. I’m trying to make something new every day. You get a little tired of making the same instruments, and tableware after a while! I tried to make many different items with bangjja craft, such as candle holders and plates, wine coolers and dishes that are not just round. I tried also making rings and bracelets and such, but all the jumul factories would copy me, so I stopped making them.

- That’s right, with bangjja nothing is ready-made. You first have to get the raw materials (copper and zinc) and melt them together in the right proportion to get to 1200 degrees Celsius. Then you pour it out onto plate frames, and mould it together and then start pounding the plates while they are hot. I think this is the most important part but also the most difficult. To know when to take the plate out from the fire before it melts away completely, and once taken out, knowing how many times you can pound it before it breaks is very tricky. This is something you can only learn by experience, by feeling the right temperature on your body for example. After more heating and pounding, you dip the piece in room temperature water, where the form you have worked so hard to create loses its shape, but this will make bangjja impossible to break. Then you must hammer it one last time to get the final perfect shape and polish it with a hand grinder. My favourite part is seeing the end result, creating a form that I imagined in my head after going through this entire process.

4. 종

(jong)—singing bells for a traditional Korean musical event

4. 종

(jong)—singing bells for a traditional Korean musical event

5. 항아리 (hangari)—a small jar

5. 항아리 (hangari)—a small jar- DIALOGUE

- CRAFT INDEX

- Because it is such a labour-intensive process, done in such a harsh environment, do you have any young

people coming to learn the craft?

- I’m sure no one wants to be in such harsh environment, in such heat! In my studio, I find that people who came here to learn often give up and leave. But, now I have one young man who’s been with me for about two years, he can now make two kkwaenggwari and two jing by himself in a day, which is very impressive. I would say there are less than 10 people who have mastered the technique from me and are now active on their own. And that’s not enough people - I have a feeling it’s a craft that will be lost and forgotten in the future.

- Unlike Japan, we do not get much funding from the government dedicated to preserving traditional crafts. Because I hold this intangible cultural heritage certificate for the region I do get a small grant from the government to teach bangjja. However, I am the one of the very few teachers for this craft and sadly I cannot teach everyone who comes to me to learn and support all the facilities by myself financially. I am always open to working and collaborating with others. Years ago when I was much younger, foreigners used to come to me to learn bangjja craftsmanship, my attitude was that this craft should only be practiced by Koreans, because it’s from here. But I was foolish to think like that, because craftsmanship belongs to everyone no matter where they are from, it belongs to anyone who wants to learn it and continue it. I really hope there will be lots of young people who are creating even more beautiful products with bangjja craftsmanship in the future and trying to make new designs with it.

JONG DUK LEE

www.bangjjayougi.com

RYUTARO YOSHIDA

www.timeandstyle.nl

JONG DUK LEE

www.bangjjayougi.com

RYUTARO

YOSHIDA

www.timeandstyle.nl

- DIALOGUE

- CRAFT INDEX

Because of its unique composition, bangjja is known to be self-sterilising and the way it conducts heat means it can keep hot food hot and cold food cold for long periods. Bangjja however, is not only used in tableware, it is also applied in the creation of a Korean traditional instrument called jong (a type of a gong). The jong, hand-forged by bangjja artisans, can be customised to make different tones through different shapes and thicknesses of the instrument’s design. This hand-made process is seen as a work of art and a traditional custom in Korea that continues to be coveted.

Bangjja brassware is produced using techniques that have been handed down over thousands of years. These products are so hardy that even pieces made centuries ago are rarely bent or broken. Today, Korean people are increasingly recognising the benefits of brass tableware, but most products on the market tend to be machine-made using a process called jumul. While bangjja brassware requires a more labour intensive and expensive process to make, it is a better product that is longer-lasting. The rare craft behind it should not be forgotten.

© Images provided by

– Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation

– Cultural Heritage

Administration

Ryutaro Yoshida

Ryutaro Yoshida