Studies in the UK opened Jungjoo Im’s eyes to the world of international design, but when he returned to Seoul

his focus became on creating products that had a universal appeal, yet referenced local tradition. His work with

Korean timber in

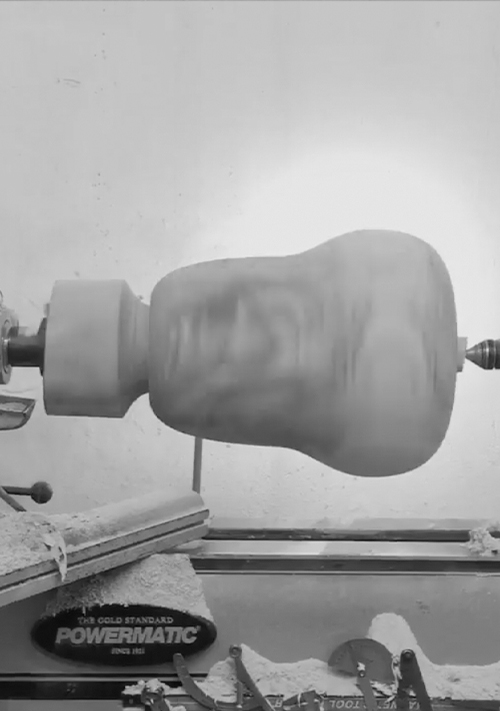

the creation of his decorative objects is experimental, but tends to emphasise hand-shaped craft, drawing upon

the traditional wood turning technique of

craftsmanship. His unique

approach is

highlighted in his noneloquent project, which was recently displayed at the

, and challenged the notion of conventional form in

creating designs that

were deliberately devoid of function. His work reflects a mood among contemporary Korean designers challenging

the norms of their industry, which typically makes objects purely for function.

Australian industrial designer Henry Wilson’s work, which includes product

commissions from skincare company

Aesop and furniture for

high-end Sydney restaurants, similarly pays attention to the importance of form. The sand-casted bronze

objects he’s become known for all marked individually by the tactile, changeable nature of the rich material

and the sculptural quality

of his designs. Yet, despite being beautiful pieces to behold, Wilson’s work tends to always serve a

democratic utility, blurring the lines between function and ornament.

Wilson and

Im speak about the making

techniques behind their meticulously produced works and the similarities and differences in their creative

processes.

1.

1. 2.

2. 3.

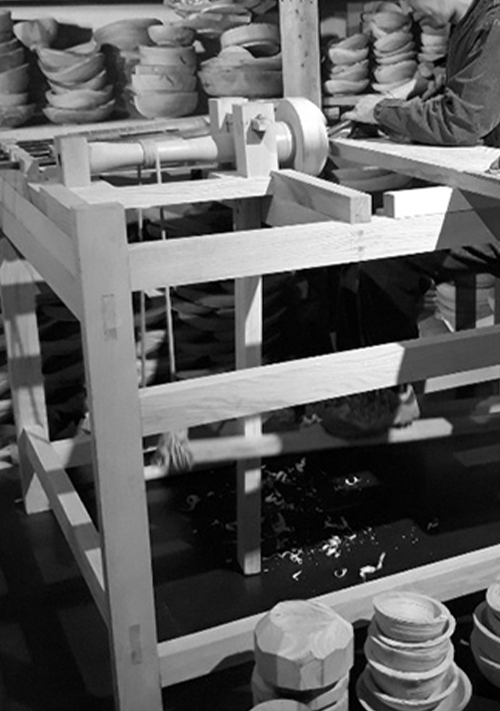

3. 1. 'Noneloquent' project in different types of Korean timber and sponge

1. 'Noneloquent' project in different types of Korean timber and sponge 2. 'Noneloquent' (coloured wood edition) made by using Korean timber 먹감 (meogam) tree

2. 'Noneloquent' (coloured wood edition) made by using Korean timber 먹감 (meogam) tree 3. A few objects from the 'noneloquent' project being used in space

3. A few objects from the 'noneloquent' project being used in space Jungjoo Im

Jungjoo Im Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson  4.

Exhibition at

4.

Exhibition at  5.

One of Noneloquent objects in fiberglass, displayed at Kkotsul (traditional Korean bar)

5.

One of Noneloquent objects in fiberglass, displayed at Kkotsul (traditional Korean bar)